The City of Mud and Books

The three-sided city of Selussin huddles between the desert and the mountains, in the shadow of the abandoned Patric castle of Revanchard. Once it was a great centre of learning and trade, but at the time of The Books of Outremer the years of war have driven the trade caravans to find other routes. The city itself endures:

Marron gazed up at the baked mud of the arch above the gate and thought he could feel how ancient this place was, and how weary as it faced yet another force of men, yet another invasion.

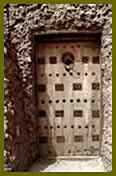

Photo by E. Condominas/UNESCO

[Jemel's] bare feet walked on cool and coloured tiles, while the walls were richly hung to hide their simple brickwork; jewels sparkled in tapestries that were faded with age, but still vivid within their folds. One room they passed was lined from floor to ceiling with more books than he had ever seen in his life before, more than he had imagined to be within the world.

This juxtaposition of the poorest building materials with the richest adornment sounds like pure fantasy: yet there is such a city, not in the lands known to the Crusaders as Outremer, but in Mali in west Africa - Timbuktu, now recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage site.

This juxtaposition of the poorest building materials with the richest adornment sounds like pure fantasy: yet there is such a city, not in the lands known to the Crusaders as Outremer, but in Mali in west Africa - Timbuktu, now recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage site.

The golden age of Timbuktu as a centre of trade and learning was several centuries after the time of the Crusades: it flourished in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. But its origins go back to the period of Outremer: one account interprets the name Timbuktu as Buktu's Well, and tells how Buktu, a Tuareg woman who was grazing her flocks, found an oasis and decided to settle there permanently. She dug a well which soon became a stopping place for nomads. Whether this is literally true or not, Timbuktu was founded as a camp by Berbers around 1100 C.E., because of its proximity to the Niger River (a major highway as well as a source of water), and its position on the long-established trade route across the Sahara. Caravans quickly began to haul salt from mines in the Sahara Desert to trade for gold and slaves brought along the river from the south.

A fascinating and informative page about Mali on the Museum of Virginia website describes the practice of "silent trade":

Arab and African traders brought salt from the north and upon arriving at the trading place they would spread out their goods and announce their presence by beating on a drum called a deba. They would retreat and traders bearing gold would arrive laying out amounts of gold dust next to the salt or other goods as payment and then depart. When the first group returned, if the amount of gold was sufficient they accepted it and left. If not, they would leave everything untouched and wait for more gold to be put out.

In 1312, Mansa (that is, Emperor) Moussa ascended the throne of the Mali Empire. He was both devout and ambitious. During his reign, the empire expanded far across Africa, absorbing a number of independent city states, among them Timbuktu, with its pivotal position. Then, in 1324, the emperor undertook the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that is the duty of every pious Muslim. But Mansa Moussa's pilgrimage was the stuff of legend: during the eight months of his journey, he was accompanied by an entourage of 60,000 people and 200 camels, all laden with food, with clothing, and with gold - by one account, more than two tons - which he distributed so lavishly that the value of gold on the Cairo market took several years to recover! Mali, and Timbuktu in particular, became famous for its wealth throughout the whole Islamic world. The map of Africa in the fourteenth century Catalan Atlas marks the city with an image of the Emperor, enthroned, holding a nugget of gold.

In 1312, Mansa (that is, Emperor) Moussa ascended the throne of the Mali Empire. He was both devout and ambitious. During his reign, the empire expanded far across Africa, absorbing a number of independent city states, among them Timbuktu, with its pivotal position. Then, in 1324, the emperor undertook the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca that is the duty of every pious Muslim. But Mansa Moussa's pilgrimage was the stuff of legend: during the eight months of his journey, he was accompanied by an entourage of 60,000 people and 200 camels, all laden with food, with clothing, and with gold - by one account, more than two tons - which he distributed so lavishly that the value of gold on the Cairo market took several years to recover! Mali, and Timbuktu in particular, became famous for its wealth throughout the whole Islamic world. The map of Africa in the fourteenth century Catalan Atlas marks the city with an image of the Emperor, enthroned, holding a nugget of gold.

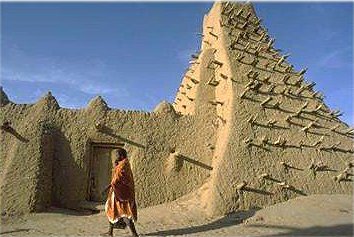

Mansa Moussa's pilgrimage was not simply an excuse to display his wealth and power; rather, he used it as the foundation for further pious works. He persuaded (and paid) the architect Abu Ishap Es-Saheli Altouwaidjin to return with him to Timbuktu and undertake the construction of the Djingareyber Mosque, the oldest of the city's three historic mosques. It is a magnificent and complex building, with three inner courts, two minarets and twenty five rows of pillars aligned in an east-west direction, yet its building materials are not costly, or even inherently durable. With the exception of a small part of the northern facade (which is built of limestone), the Djingareyber Mosque is made entirely of banco - earth mixed with organic materials such as fibre, straw and wood - or, in other words, mud.

In Hand of the King's Evil, Elisande ventures:

on into the shadow of the greatest temple of Selussin, a three-sided tower - of course, three-sided - built of mud reinforced by a framework of wooden beams, whose ends jutted irregularly from the heat-baked, crumbling walls. In this high hot season, every day left its debris; every winter, or so she'd heard, the people would slather fresh mud between the beams to repair the ravages of another summer's sun.

The ravages of the sun, and those of the desert too; in addition to the inherent fragility of mud as a building material, the Djingareyber Mosque is vulnerable to encroachment by the desert on whose edge it stands. In 1952 the sands reached right up to the foot of the mosque: "So the roof had to be taken down and the walls raised", in the words of Ali Ouid Sidi, head of the Timbuktu Cultural Mission. But even routine restoration has to be carried out every other year, and there is a vivid description of this process on the page devoted by UNESCO to this World Heritage Site. The process seems to be part religious ritual, part community festival - and part serious labour. The masons' guild begin by choosing a master mason

who, well armed with magic spells, applies the first clods of banco while the others chant incantations. The initiated say that this ritual is crucial to ensure that the work is done well and safely. As they point out, there have been no deaths or injuries in living memory of the inhabitants of Timbuktu.Once the master mason has formally initiated the work, starting always with the minaret, the more-or-less voluntary workers can join in:

Under the supervision of the older citizens, young people and adults formed a chain to pass the banco from hand to hand to the sound of beating drums and flutes. The griots (members of the caste of poet-musicians who ensure the transmission of the oral tradition) also came to fire the enthusiasm of the participants. Since mosque restoration work is a religious and social obligation, people of all ages are mobilised and sometimes reluctant participants are taken to the site by force, as occurred in 1996.

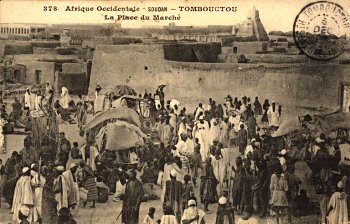

Timbuktu grew and prospered as a trading centre. Its fabulous wealth was based largely on the trade of gold, salt, ivory, kola nuts, and slaves. Chaz Brenchley's Selussin, too, was once a centre where rich goods were traded:

Timbuktu grew and prospered as a trading centre. Its fabulous wealth was based largely on the trade of gold, salt, ivory, kola nuts, and slaves. Chaz Brenchley's Selussin, too, was once a centre where rich goods were traded:

The great open area below the temple would have been like a confluence of many waters, where caravans came together from all over the known world; big as it was, it could hardly have been big enough. It must have seethed with crowds, with colour, with merchants crying the value of their silks and jewels, their spices, their camels and slaves. Now the people traded only with themselves, and only what little they could spare.and the marketplace has become a wide and wasted space.

The Selussin of Hand of the King's Evil was already in decline at a time when, in our world, Timbuktu was only beginning to bloom; and even in the sixteenth century, after the time of its greatest glory, it could impress as travelled a visitor as Al Hassan Ibn Muhammad Al Wazzan, better known by the nickname Leo Africanus. He was born in Granada, but joined the Islamic exodus from that city after its reconquest by the Christians, settled in Fez and travelled extensively in Africa. His description of Timbuktu remarks on the contrast between the magnificence of the buildings and the humble materials of which they were built:

The houses here are built in the shape of bells, the walls are stakes or hurdles plastered over with clay and the houses covered with reeds. Yet there is a most stately temple to be seen, the walls whereof are made of stone and lime; and a royal palace also built by a most excellent artist from Granada.He described the legendary royal hoard of gold, and the skilled artisans who manufactured fine cloth and other goods for trade. Yet it was another form of commerce altogether which impressed him with its prosperity:

Here are great store of doctors, judges, priests, and other learned men, that are bountifully maintained at the king's cost and charges. And hither are brought diverse manuscripts or written books out of Barbary, which are sold for more money than any other merchandise.

The wealth of the city of Timbuktu, the piety of its rulers, its position at the centre of Africa's trade routes: these factors encouraged scholars to settle in Timbuktu, bringing their books with them, and then to draw in more books from North Africa and Egypt. With such a ready market for books, Timbuktu became not only an importer of books, but also a place where books were written and copied: texts on theology and law, studies of the Arabic language, learned Qur'anic study and pious poetry in praise of the prophet were not only written in huge numbers but also, astonishingly, survive. These hidden treasures have only recently been revealed to outsiders, for although Askiya Dawud (ruler of Songhay from 1549 to 1583) is claimed to have established public libraries in his kingdom, the great treasures of Timbuktu are the private collections.

[Examples of manuscripts from the Fondo Kati collection have been removed from this page at the request of the Fondo].

Marron and his companions, delayed in Selussin through no choice of their own, leave the town without regret; Timbuktu has become a byword for the remote and the enticing, and travellers through the centuries have gone to great lengths to visit it.

Background motif based on the hand reliquary of St. Nicholas in the collection of the Cilicia Museum, located within the Armenian Patriarcate in Antelias, Lebanon.

Used by kind permission of the Museum.