The Man who United the Tribes

The greatest threat to the kingdoms of Outremer is that the tribes of the Sharai may unite against them. Like the historical Crusaders, they have profited from the disunity of those who rule the land, who would as soon fight their neighbours as the foreign invaders. In the Books of Outremer, there is one man who succeeds in bringing together men from all the tribes to attack the Roq de Rançon, the charismatic Hasan:

"He leaned forward to cut at the blistered, blackened meat, and his face was lit by the fire's glow. Shaven cheeks, a sharp hooked nose above a neat beard, white teeth and glittering, hooded eyes: Jemel wondered what it was about this man, what power he carried in his voice that could make so many listen and believe, and ride together to follow him against all custom."This romantic figure seems too irresistible to be real; and yet he has a historical equivalent in Salah ed-Din Yusuf ibn-Ayub, known to the West as Saladin.

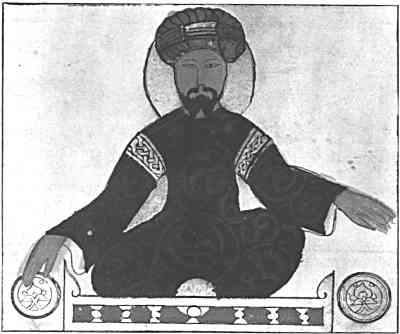

Saladin did not have the physical good looks of the romantic hero. Steven Runciman draws on contemporary accounts to describe him:

"He was short and stout, red-faced and blind in one eye; and his features revealed his low birth. But he was a soldier of genius; and few generals have been so devotedly loved by their men."Saladin's family were not poor; his father, Ayub, was the military commander of the city of Takri, but this appointment was dependent on the goodwill of more powerful men. Yet Saladin first ended the political and religious division between Egypt and Syria, then proceeded to make himself master of both countries. He drove the Christians out of Acre, Beirut, Sidon and finally Jerusalem itself. And, as Geoffrey Hindley remarks in his biography:

"Saladin is one of those rare figures in the long history of confrontation between the Christian West and Islam who earned the respect of his enemies."- more than respect, indeed, for Saladin soon became the subject of romantic fictions among those who were in theory his enemies: one thirteenth century tale creates a romance between Eleanor of Aquitaine and Saladin (who was eleven years old at the time Eleanor accompanied her husband on the Second Crusade).

Saladin was born in the year 532 of the Islamic calendar (September 1137 - September 1138 C.E.). His family came from the Kurdish Rawadiya clan, and throughout his life there were those who saw him as an outsider and resented his success because of this. His father, Najm ed-Din Ayub, had been appointed commander of Takri through the influence of a friend of his father, Saladin's grandfather. Ayub appears to have been a wily politician, but in 1138 he was obliged to flee from Takri to the court of Imad ad-Din Zanghi, the governor of Aleppo and enemy of his former benefactor: there is a legend that Saladin was born on the very night when his father departed from Takri under cover of darkness.

Yet the family continued to prosper under Zanghi's son Nur ad-Din (Nureddin in the Westernised form of the name). Ayub became governor of Damascus and by the time Saladin was 18 he had joined the army, became part of Nur ad-Din's personal entourage and been given a post in the administration of the city. Little is known about this period of his life, and some of what is known is negative. Between 1157 and 1161, Saladin's father and his uncle Shirkuh led three caravans to Mecca; the pilgrimage to Mecca is a binding obligation on a pious Moslem, yet Saladin did not take the opportunity to accompany them, even on the last occasion when Nur ad-Din was one of the party. Perhaps he had business at home that he was unable to leave; or perhaps he was not as pious as he later became. Baha' al-Din Ibn Shaddad, who knew Saladin personally and wrote a biography of him, reports him as saying that when he became vizir of Egypt "in recognition of the blessings that God had vouchsafed to him, he gave up wine and the pleasures of the world" - presumably, until this ennoblement (when he had already turned 30) he was not so abstemious. As a young man, he had a reputation as a polo player, and he continued to enjoy hunting.

In 1163 Amalric, the Christian King of Jerusalem, invaded Egypt, on the pretext that an annual tribute of 160,000 dinars had been agreed but never paid. Egypt appealed to Nur ad-Din for help, and after some hesitation he sent an army under his trusted lieutenant Shirkuh, who was accompanied by his nephew Saladin. During this campaign, Saladin played a leading rôle, holding the city of Alexandria through a month-long siege and negotiated surrender. During these negotiations Saladin came for the first time into amicable contact with the Christians: later, rumour claimed that he had been knighted at this time by Humphrey of Toron. On this occasion, the army returned to Damascus, but when, in 1168, the Franks once again invaded Egypt, Shirkuh - again accompanied by his nephew - drove them out, but, instead of withdrawing, deposed the corrupt and unpopular vizir and declared himself vizir and king of Egypt.

Within months of seizing power, in March 1169, Shirkuh died - allegedly of overeating - and was succeeded by his nephew Saladin.

In 1174, on the death of Nur ad-Din, Saladin rode north, protesting his loyalty to Nur ad-Din's eleven year old son, Malik as-Salih Ismail. He was welcomed in Damascus, and after he had spent his first night there in the house which had been his father's, the citadel gates were opened to admit him, and he was able to install his brother as governor in as-Salih's name. He met more resistance from as-Salih's refuge of Aleppo, but after an unsuccessful siege of that city, turned his attentions elsewhere, and gained control of most of Syria. From this position of strength he repudiated his allegiance to as-Salih, and proclaimed himself King of Egypt and Syria. Finally, when Saladin had conquered all the surrounding country, including the great fortress of Azaz which protected the city to the north, he was able to force an agreement with Aleppo. According to Runciman, when the treaty had been signed, as-Salih's little sister visited Saladin's camp. He asked the child what she would like as a gift, and when she replied "The Castle of Azaz", made the characteristic gesture of returning it to her brother. Saladin then returned to Damascus, where he celebrated his marriage to Asimat ad-Din, widow of Nur ad-Din.

It was over ten years before Saladin was ready for the final onslaught on the Christian interlopers; but in June 1187 he crossed the Jordan and captured the city of Tiberias. The Christian army rashly abandoned their camp to march through the blazing summer heat and met Saladin's forces at Hattin: where they were crushingly defeated, and the relic of the Holy Cross which the Bishop of Acre had carried as a standard into battle was captured. With this impetus, Saladin captured the cities of Acre, Nablus, Jaffa and Ascalon, and by September his forces were outside the walls of Jerusalem.

It was thanks only to Saladin's courtesy that Jerusalem had a military commander. Balian of Ibelin had been stranded at Tyre after the defeat at Hattin, but his wife (the Byzantine princess Maria Comnena) and family were in Jerusalem. He asked Saladin for safe-conduct to go to Jerusalem and escort his family back to Tyre, and Saladin consented, on condition that Balian spent only one night in Jerusalem, and swore never again to bear arms against him. But when Balian reached Jerusalem, he found the Patriarch and city officials desperately trying to organise the city's defence. They begged him not to abandon them, and the Patriarch told him he had a religious duty to break an oath to an unbeliever in order to help his fellow-Christians. Balian wrote to Saladin, explaining his dilemma, and Saladin not only forgave him, but sent an escort of his own troops to accompany Maria Comnena to Tyre. Balian could not save Jerusalem for the Christians, but Saladin was similarly merciful to the city, and the Christians were treated as prisoners to be ransomed rather than as infidels to be slaughtered.

The fall of Jerusalem revived the call to arms in Europe. In 1191 Saladin lost Acre, and in 1192 he signed a truce with England's King Richard I. He died the following year, and the empire he had assembled did not long survive him.

- In addition to Steven Runciman's indispensable History of the Crusades, I have drawn heavily on Geoffrey Hindley's Saladin: a Biography (Constable, 1976) and Chronicles of the Crusades edited by Elizabeth Hallam.

- Amazon list a number of other books about Saladin, among them P.H. Newby's Saladin in His Time and Tariq Ali's novel The Book of Saladin.