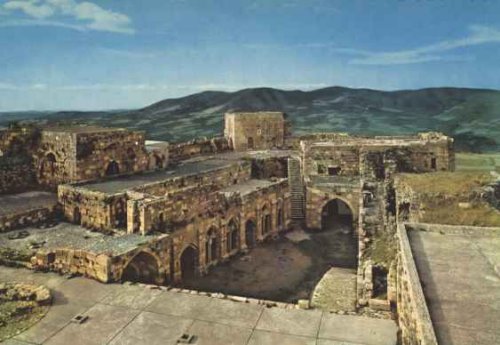

The castle shown in the picture above, and in the plan on the home page, is the castle of Krak des Chevaliers, in the Crusader state of Tripoli (modern Syria), which T.E. Lawrence described as "perhaps the best preserved and most wholly admirable castle in the world". Like the castle of the Roq de Rançon, it stands on a massive outcrop overlooking the plain, and incorporates the remains of an earlier castle, known as Hosn al-Akrad, the Castle of the Kurds, after the Kurdish soldiers garrisoned there in the eleventh century. Crusaders, commanded by Tancred of Antioch, captured it in 1110, and began a process of strengthening and enlarging the castle, until it could house a garrison of 2000. It was repeatedly attacked by the Saracens - in 1188 Saladin reportedly examined its defences and moved on without attempting to besiege it. Meanwhile, Krak passed into the keeping of the Count of Tripoli, who handed it on, in 1142, to the Knights Hospitallers (like the Templars and the Ransomers, a military religious order) from whom it took the name "des Chevaliers". They held it for 130 years, until it was besieged and, after a month-long siege, captured by the Sultan Beibars, on April 8th 1271.

The castle is designed to be above all a stronghold, and is constructed on a variation of the standard medieval motte and bailey plan. In its simplest form, this consists of an earth mound, or motte, with some sort of palisade on top, surrounded by an outer wall, or bailey, creating - or, more often, reinforcing the protection offered by the natural terrain - a protected space into which villagers or livestock could be gathered when threatened. At Durham, in northern England, the earth mound is combined with a naturally defensive position across the neck of a peninsula formed by the river Wear. The keep is now of stone, not wood (a technical development displayed, for obvious reasons, in most of the castles which survive to the present day) and the streets of North and South Bailey reveal the outline of the area which could once be enclosed and defended. The diagram below shows two variations on the same theme, each being a castle with protected inner and outer wards, living accommodation within the walls, including its own chapel, and a tower or keep which could hold out for a while even if the rest of the castle fell.

The sketch on the right is, again, the ground plan of Krak des Chevaliers. That on the left is Château Gaillard in Normandy; it was built by Richard the Lion Heart, in his capacity as Duke of Normandy, to defend his territory against the King of France. In building it, Richard put into practice ideas about fortification which he had brought home from the Crusades. Château Gaillard took only a year to build, and Richard is said to have been so delighted with the strength and rapid construction of his new castle that he boasted of his "lusty, one-year-old daughter"!

Stories like this confirm the impression given by external photographs of Krak: that it is, above all, a fortress, designed for strength rather than beauty. Yet Robin Fedden perceives a harmony of form and purpose in this mass of masonry:

From the summit of the redoubt the size and cunning of Krak can be fully appreciated. The sensation, as the wind whistles over the battlements, is not unlike that of being on the bridge of a ship, and the fortress seems to ride above the extended landscape with a ship's poise and mastery. There is the same strength, together with the same precision of design that, transcending the utilitarian, creates a work of art.

Within the massive fortifications, the Knights Hospitallers built themselves a home. They provided it with all necessities - stabling for their horses, warehousing for their stores, a windmill on the north wall to grind corn for their bread - but they also made their buildings as beautiful as they could.

The large hall on the left of the courtyard in the picture above was probably used for meetings and as a reception room; it is divided from the courtyard by an arcaded corridor whose elegant stone tracery has been compared to carving found at Rheims. Steven Runciman, considering the aesthetic aspects of Crusader life in his History of the Crusades gives pride of place, among the buildings of the invaders, to Krak:

But the castles in the East had their aesthetic value. Their chapels are amongst the best examples of the ecclesiastical architecture of Outremer. Their Great Halls, of which the loveliest is at Krak, are comparable with the best early Gothic Halls of western Europe. Their residential quarters, which survive to give us some idea of the palaces of the nobility of Outremer, show delicacy and taste. The chamber of the Grand Master at Krak, high up in the south-west tower of the inner enceinte, with its ribbed vaulting, its slender pilasters and its simple but well carved decorative ornamental frieze of five-petalled flowers, was perhaps more elegant than most rooms in the great fortresses, but it must have been paralleled in the richer castles and palaces in the towns.

or, in the rather quaint English of the 1966 Guide to Krak:

A fine staircase leads to the second floor where there is that is which is called the Master's lodgings. It is a circular room receiving light through a rectangular window, at the North-West and through a very big window with broken arch at the South-West.

The decoration of this room is of curious style.

Its vault is a cupola forming a perfect semicircle, under which is bended an ogival casement falling on 4 capitals supported by little columns. The spiral staircase of this tower leads to the terrace where from we can have an admirable view of all the fortress and the surrounding landscape.

A suitable place, in fact, for the daughter of the King's Shadow to spend her wedding night!

Behind the courtyard, in the centre of the picture above (and on the far left of the general view of the castle at the top of the page) is one of the oldest surviving parts of the building: a square tower known as the Tower of the King's Daughter.

|

|

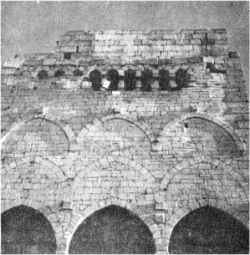

The origin of this name is unexplained. The photograph on the left shows an arcaded window, and a door opening onto the ditch between the inner and outer walls of the castle. The north-west façade is also elaborately arcaded. The Guide says, tantalisingly, that "we are planning to transform the upper room into a resthouse for the visitors of the Krak."

The web has a rich variety of information about medieval castles: there is a general overview which is a good introduction to the subject, despite numerous typographical errors. The tourist office of Les Andelys publishes a number of pictures of Château Gaillard. An internet search turns up numerous visitors to Krak des Chevaliers, who have recorded their impressions ans posted their photographs. You can even buy a book which will enable you to build your own Crusader Castle.

I am grateful to Mary Sales for the loan of Crusading Warfare by R. C. Smail (still available in a more recent edition updated by Christopher Marshall), Crusader Castles by Robin Fedder and John Thomson, and above all for her postcards and The Krak of the Knights: Touristic and Archaeological Guide by Abdulkader Rihaoui, translated by Safya Sassy. These materials have contributed substantially to the revision of this page.